While the debate around the use of super for nation-building projects like affordable housing rages, HOPE Housing is working on a new way for funds to get involved.

Lachlan Maddock

HOPE (Home Owners’ Partnering Equity) Housing is aiming to solve a problem familiar to anybody living in Sydney or Melbourne: finding an affordable house that isn’t light-years from where you live, and doing it for essential workers – nurses, midwives, police.

While most proposals for super’s involvement in affordable housing have either focused on debt funding for housing projects or direct investment in their construction, HOPE’s solution is a shared equity contract, distributed through banking partners like Police Bank, with HOPE co-investing up to 50 per cent of the value of the house.

“I really feel that this is going to be a worldwide phenomenon that we’re creating in Australia,” says Tim Buskens, HOPE CEO “We’re bringing in the next generation of house/home financing into the market and we’re looking at that 95 per cent debt to 5 per cent equity ratio (taken on by mortgagees) and bringing it back down – but bringing it back down by opening up a $10 trillion property market with minuscule access to it… There’s philanthropy out there, but institutional capital has to be attracted to a solution of this type; you can’t ask them to take anything less than a commercial return.”

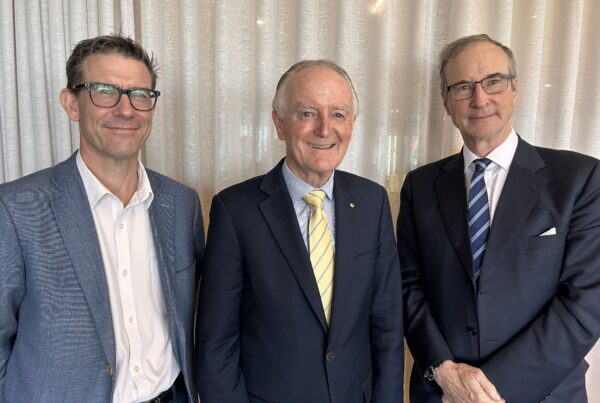

HOPE was formed by Buskens and Pacific Equity Partners co-founder Tim Sims. It currently has three homes, ranging between $1.04 million and $2 million, and several more in the pipeline. Buskens calls the model “attainable housing”. Liquidity comes from partial buybacks or refinancing, as well as home sales.

“Our stake is a pure equity stake,” Buskens says. “We’ve agreed terms with the bank that we’re completely Pari-passu with them, so they’ve got no claim over our equity; it’s a pure equity slice. We take appreciation of the capital growth in the home when they sell; depending on what our stake is, but let’s say 50/50. When they sell, we get 50 per cent of the upside, and if they sell at a loss, we take a 50 per cent of the downside.”

“Our investment philosophy is very similar to how Australians have built wealth, which is a geared growth position in residential property. Because we’re completely Pari-passu at the home level with the pure equity, at the fund level we’re enhancing the market growth by mixing in a debt facility. So that helps us target a commercial net IRR of around 10 per cent annualised long-term growth.”

While Buskens is hoping to attract superannuation funds to the solution – HOPE is currently focused on building a track record – its seed investors already include an array of family offices and other high net worth investors.

“When you innovate in Australia you need to look at the first mover group and the second mover group. The first mover group in Australia is relatively small,” Buskens says. “These are people that think not only about the investment fundamentals – the ten per cent (return) – and they don’t think only about the social return of helping essential workers that help us, but they can see the bigger picture, which is the innovation in this space. Or they’re used to investing in things that are groundbreaking.”

HOPE’s solution comes at a unique time for the long running debate around how – and whether – superannuation should be involved in housing. That debate goes back to the start of compulsory super; Paul Keating himself promised superannuants that they would be able to draw down as much as $10,000 from their super to purchase a house, but later dropped the idea in the face of stiff opposition from unions and the industry.

The question of where superannuation fits into the housing question has more often been the domain of those painted as super’s enemies – conservative thinktanks and the Liberal/National Party, with their proposals to use superannuation for housing knocked back as either proposals to weaken the superannuation system or ones that would only heat up the housing market even more. Investment in affordable housing itself has been scarce, aside from a few direct investments by funds like Aware, with funds daunted by the lack of performance data and how the asset class is treated by the Your Future Your Super performance benchmarks.

“Superannuation is a scale investment, and it has to have the ability to go into investments and markets that they understand and where there is a well-documented track record and understood risk/return profile,” Buskens says. “In the competition for capital, there are easier and quicker decisions to be made elsewhere to deliver that sort of return to investors than there are in housing. You see leaders in Aware and other funds, but in a portfolio that’s now hundreds of billions of dollars this is a small slice of a big pie.”

Still, The Albanese government’s Housing Accord attracted its share of critics, who believe that super funds investing on the basis of anything other than financial returns violates the sole purpose test. But Buskens says that the industry and its critics have “partially forgotten what (the sole purpose test) actually means”. All investments must obviously be considered through the lens of what is commercially viable, but that doesn’t mean automatically ruling out investments that have a positive social effect.

“What we should be doing is looking at the stability of all the pillars,” Buskens says. “When there’s one pillar that can support the others, for the better of retirement, while at the same time delivering a commercial return, surely there’s an argument that there’s a role for super to play there.”

“Keating and (Treasurer Jim Chalmers) are thinking this way; that it’s not just about finding the highest return generating infrastructure asset in the world. That there’s assets with a risk/return profile within the bounds (of acceptability) with a purpose in terms of social and community infrastructure that will support retirement.”

Article originally published on Investor Strategy – Tuesday 24 January 2023