Early on in your career you were at the forefront of PropTech innovation in Australia, particularly in the development of hedonic indexes. How has this shaped your current work?

Prior to my academic career, I worked with a residential housing fund manager focused on democratising housing investment—much like HOPE Housing. Through our interactions with institutional investors, we recognized that the pricing of housing was poorly understood. We realised that solving this issue would be crucial in developing an institutional-grade investment product.

At the time, despite housing being Australia’s largest asset class, centralised information on the sector was limited. Data is essential to any investment decision-making process, and early in our journey, we responded to a ‘call to arms’ from the RBA governor for market participants to innovate and deliver better data and measurements for house prices.

This led to a joint venture with RP Data (now CoreLogic) to develop Australia’s first house price indices. Our goal was to build a model that accurately captured the true measure of house price growth across ten million properties nationwide. This effort resulted in pioneering the first hedonic imputation house price index.

Unlike stocks, bonds, or other financial instruments, housing is not a fungible asset. There is no house in Australia that is identical to anyone else’s – even in large developments, for example, each unit has a slightly different aspect to the sun. A hedonic imputation index addresses this by breaking down non-fungible assets into their fungible components, allowing us to capture the true underlying growth of the housing market.

Can you elaborate on the concept of the hedonic home index and its role in facilitating institutional investment opportunities?

Imagine comparing two very different houses—one large with a pool, and another smaller but located in a more desirable neighbourhood. Directly comparing their prices or tracking how their values change over time is challenging because they are not identical.

A hedonic imputation index addresses this by breaking down each house into its key features—such as the number of bedrooms, backyard size, presence of a garage, or proximity to good schools. Each feature is assigned a value based on how much buyers are willing to pay for it. The index then uses this information to adjust prices, making it possible to fairly compare different houses or to track the value of these features over time. This allows us to compare homes that aren’t the same by considering all the individual elements that contribute to their value.

The introduction of such indexes opens up new avenues for innovation in the housing market, such as the development of derivatives. These financial instruments could enable institutional investors to participate more actively in the housing market. Traditionally, the housing market has been highly decentralized, with little need for a portfolio-based approach to risk management. However, as institutional investors begin to take larger stakes in the market, the establishment of a derivatives market would be beneficial, allowing these investors to manage risk more effectively.

In the United States, the Case-Shiller Index has paved the way for real estate futures trading with the CME Group. Similarly, a derivatives market for housing in Australia would not only enable investors to hedge against risk but also create opportunities for speculation. Currently, speculation often involves purchasing physical assets, which reduces the supply available to non-speculators and drives up prices. By introducing a derivatives market, investors could speculate without directly impacting the housing supply, leading to a more balanced market.

You recently authored a paper on the impact of residential real estate on portfolio allocations. What were the key takeaways?

In asset management, portfolio allocation decisions are a crucial but time-consuming task. With the advent of Large Language Models (LLM) and Artificial Intelligence (AI), much of this work can now be automated. My research aimed to assess whether the outputs of these models are (a) accurate, and (b) whether using AI in this way provides a productivity benefit.

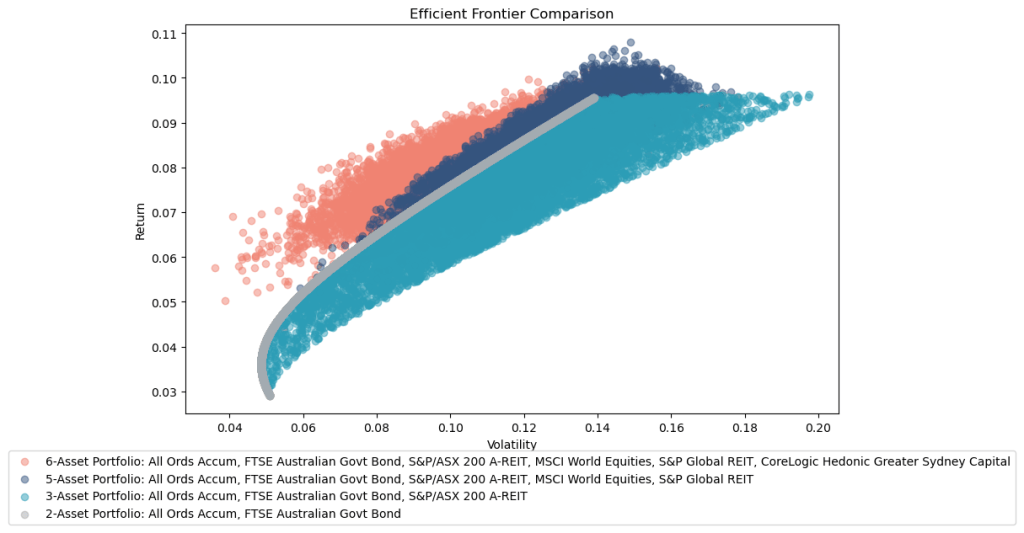

The findings demonstrate that incorporating residential real estate into a portfolio can enhance the efficient frontier, meaning it can improve returns while lowering risk. In simple terms, adding residential real estate to a portfolio can offer better returns for a lower level of risk compared to other asset classes.

Figure 1: Efficient Frontier (January 2009 to December 2023)

Source: PropTech CRC

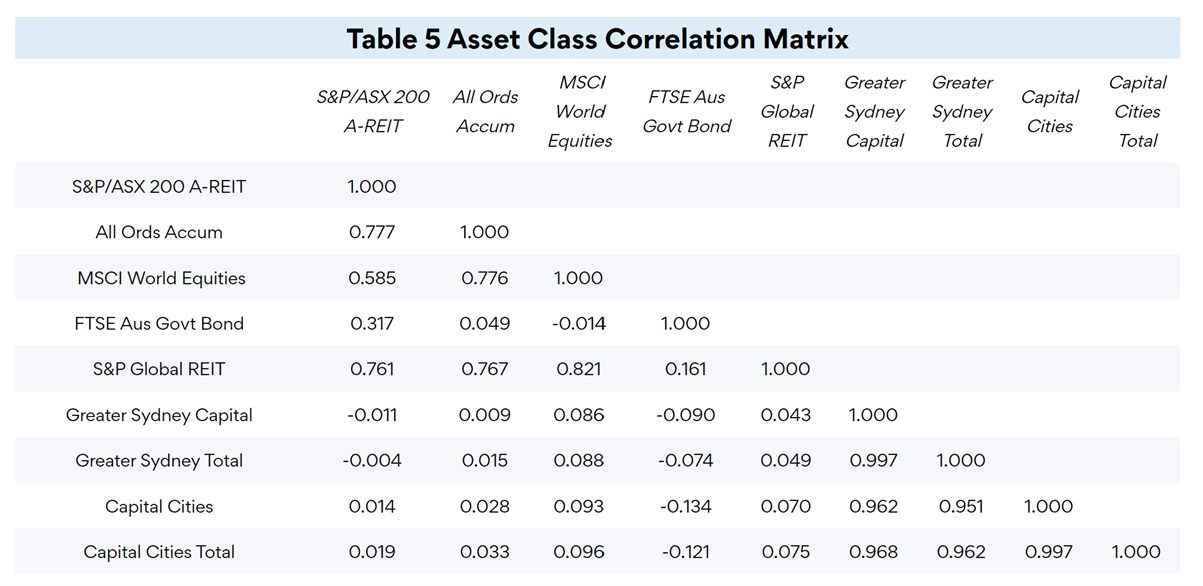

This advantage largely stems from how house prices behave at a portfolio level. Unlike individual assets, a portfolio of real estate investments is less likely to experience significant price drops. While the housing market can decline, the frequency and severity of these declines are much lower compared to equity markets. Additionally, the research found that housing is a defensive asset class based on its low correlation with many other asset classes, reinforcing its role in a well-diversified portfolio.

Figure 2: Asset Correlation Matrix

Source: PropTech CRC

However, it’s important to note that these results are observed at a portfolio level. A common misconception is that buying a single house will yield the same benefits, but that’s not the case. An individual house can be one of the riskiest assets you can hold. This is where housing funds offer a key advantage for investors, allowing them to reap the benefits of residential real estate without taking on the risks associated with single-property ownership.

Despite the portfolio benefits, institutional investors in Australia remain wary of investing in residential property. Why is this?

Whenever this topic comes up—whether in discussions about the Housing Australian Future Fund (HAFF) or similar initiatives—several concerns are frequently raised. These include the difficulty in accurately measuring house prices, the lack of a clear investable benchmark index, uncertainty about the liquidity profile (how gains and losses will be realised), and the common argument that many Australians already own homes, so why should super funds or similar entities invest in more housing?

These concerns can be addressed and resolved. First, the development of a hedonic house price index demonstrates that creating an investable benchmark is possible. Regarding liquidity, it doesn’t have to rely solely on the buying and selling of the underlying asset. There are multiple layers to liquidity, and derivatives could be an effective way to inject liquidity into the housing market. However, this requires the creation of such markets by industry participants.

Additionally, a secondary market for unit trusts could further enhance liquidity by allowing investors to trade units of a trust, similar to shares in a company, without needing to directly transact in the underlying property assets. This would provide a more flexible exit strategy for investors and attract broader participation by creating a more liquid and dynamic marketplace.

And while it’s true that many Australians own property, this type of investment is inherently risky, as most people can only afford to purchase a single property. A pooled fund, similar to how ETFs have pooled capital into stocks, could offer better diversification opportunities. For many property investors, a pooled vehicle might be a more attractive option than the traditional approach of being a landlord.

Tell us about the PropTech CRC initative.

Despite housing being the largest asset class in Australia, it has seen minimal digitisation—an irony, considering that Australia was a global pioneer in digitising the financial market for equities, becoming the world’s first fully electronic financial market in 1987.

The PropTech CRC aims to conduct research that enhances the efficiency and transparency of real estate markets while identifying opportunities for digitisation. Our efforts are organised into four streams:

- Stream 1 focuses on unlocking supply and improving the planning process. We are exploring how AI can be used to automate systems and enhance communication channels to streamline these processes.

- Stream 2 is dedicated to increasing access to property. This involves helping people find the right homes to buy or rent and creating more transparency around price discovery.

- Stream 3 seeks to establish secondary markets for real estate. We need to consider innovative ways to unlock capital that can drive development and foster innovation in the sector.

- Stream 4 will concentrate on connectivity—developing the digital infrastructure, or “plumbing,” that ties the entire ecosystem together.

Through these streams, the PropTech CRC aims to bring real estate into the digital age, making the market more efficient, transparent, and accessible.

Any final words?

It’s crucial to recognise that housing is not a monolithic market. Investors need to consider sub-markets such as social housing, community housing, SDA (Specialist Disability Accommodation), and market-rate housing. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution that addresses all these segments simultaneously. We need to improve our measurement of these sub-markets to better understand them and then develop products that meet both the needs of end-users and the requirements of investors.

By advancing our ability to accurately price and benchmark these sub-markets, as discussed earlier with the development of a hedonic house price index, we can unlock liquidity and create innovative solutions, including secondary markets, that bring equity-led investments into the broader housing ecosystem.

Want to learn more about investing with HOPE?

Book a meeting with Evan Hinchliffe

Head of Distribution