- Introduction

- Why home ownership

- Home ownership drives security

- Expanding access to home ownership

- Private capital

- Capital growth, not rental yield

- Strong capital growth

- Balancing ESG outcomes

- ESG credentials of home

- Institutional Investors

- Attainable home ownership models

- Residential housing models

- Additional Information

Introduction

Australia faces a persistent challenge in the realm of housing affordability, with soaring prices and limited accessibility. Amidst this backdrop, private sector solutions have emerged as a potential catalyst for transformative change. This paper builds on HOPE’s response to the Government’s National Housing and Homelessness Plan Issues Paper and explores the role of the private sector in addressing home ownership affordability in Australia1. It analyses various strategies and initiatives that harness the power of private investment to create sustainable, inclusive, and attainable home ownership solutions.

Why home ownership, not just rental relief is a key part of the solution

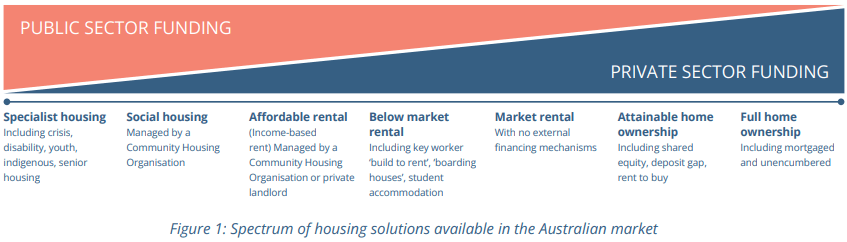

In the main, public-sector led approaches to the housing challenge have to date focussed on supply and rental relief solutions, including the likes of affordable rental, social housing, and specialist housing. We do note that federal and state governments have tried to help with home ownership with First Home Buyer (FHB) grants2, equity financed second mortgages3 and Home Guarantee Scheme (HGS)4 However, the challenge to step more people into home ownership is more widespread and nuanced than the support the government can provide. As the public sector works to refine its approach to supply side solutions, private sector players are well placed to address demand side options in both the rental and home ownership verticals.

Home ownership drives security in retirement

While rental relief is a much-needed solution for many Australians, home ownership remains the primary aspiration for many, given its criticality in retirement. As documented in Treasury’s Retirement Income Review – Final Report, the home is the most important component of voluntary savings. It improves retirement outcomes by reducing ongoing housing costs and acts as a store of wealth that may be drawn upon to help fund retirement5.

Falling rates of home ownership among pre-retirement Australians are therefore of great concern, and if not reversed, will significantly impact retirement outcomes for many. Declining home ownership rates will force retirees to increase their reliance on the Age Pension and other welfare measures to support increased housing costs during their non-working years. Treasury’s 2023 Intergenerational Report is alert to this, noting that changing home ownership trends and rising mortgage indebtedness are a fiscal risk to Age Pension spending in the future, and will impact superannuation draw down rates6.

Expanding access to home ownership

Given the central role home ownership plays in retirement, it is important that the breadth of affordable housing solutions innovate to expand access to home ownership, not just rental relief. While renting remains a critical step towards ownership, fostering renting as a long-term, entrenched housing solution has negative long-term impacts on wealth creation and retirement.

Falling rates of homeownership demonstrate, in part, that the traditional mortgage market can no longer be the only financing tool to step an increasing number of middle-income Australians into affordable home ownership, shoring up their retirement prospects. To solve for this challenge, Australia must better leverage private market capital and develop new financing solutions that increase access to home ownership, while delivering this capital a compelling and investable return

Private Capital approaches to addressing affordable housing and home ownership

The private capital pool in Australia runs deep and is estimated to be in excess of $1 trillion in funds under management7. This capital pool includes wholesale investors (High Net Worth Individuals (HNWI)), Family Offices, Self-Managed Super Funds (SMSF), and endowments (which in the Australian context typically take the form of Public and Private Ancillary Funds). Australia is also home to a world-class superannuation system with $3.5 trillion in workers savings (including via the aforementioned SMSF pool) invested across a multitude of asset classes8.

Historically, HNWI, SMSF and Family Office private capital has been the biggest supporter of direct residential property investment, having long bought into the return narrative of the landlord model. However, there is a growing body of evidence that indicates this model may not be as optimal as it once was, in maximising returns.

Analysis of residential property yields indicates that gross yield (rent) on houses in Australia, over the period 2010-2013, averaged 3.5%, according to SQM Research9. However, there are substantial running costs which need to be considered to arrive at a net yield. Analysis by Stockspot, building on RBA data sources, puts running costs (including council rates, repairs, depreciation, body corporate fees, water, and insurance costs) at 2.6% p.a.10 On this basis net yields barely approach 1%.

Outside of the direct landlord model, a new emerging investment trend in the private capital space is towards deployment of capital into fund managers that partner with operating providers who offer rental accommodation at below market rates. These investments are bucketed under the ‘affordable housing’ banner. The reduced rental income from low-income tenants is supplemented with additional income from government subsidies, ensuring investors can receive a yield that is on-par with the direct landlord model. Investment schemes under this banner include Community Housing Providers (CHP) and Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA). Given these models require government subsidies to be commercially attractive for private capital, the risk profile may be heightened, should subsidies be reduced or removed entirely.

Capital growth, not rental yield, is the key return driver in property

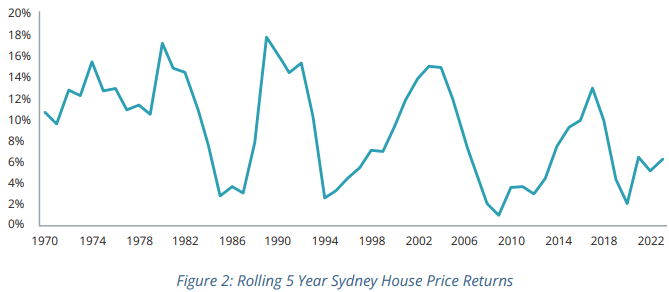

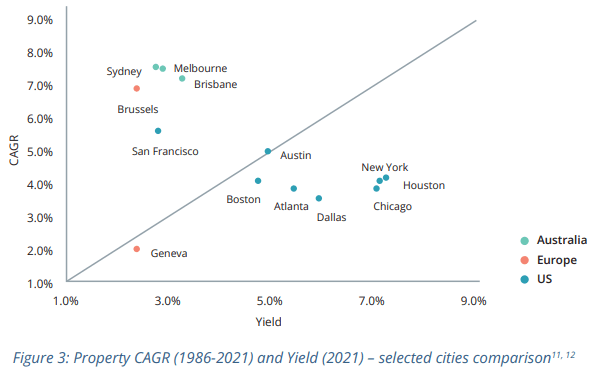

Ongoing yield compression and even negative yields in residential real estate has been tolerated by Australian investors due to favourable tax settings (negative gearing) and the remarkably strong capital growth characteristics that have persisted in capital cities in Australia for over 50 years. This is best demonstrated by analysis of Sydney house prices, which have not experienced a negative 5Y rolling return since at least 1970.

The question has always been, what has driven this growth, and will it continue? A 2023 PEXA-LongView report sheds some light on the answer to this question. It notes that, “Australia has exceptionally high population growth, a population that is concentrated in a small number of large cities, and strong macroeconomic management.

The question has always been, what has driven this growth, and will it continue? A 2023 PEXA-LongView report sheds some light on the answer to this question. It notes that, “Australia has exceptionally high population growth, a population that is concentrated in a small number of large cities, and strong macroeconomic management.

These defining characteristics of Australian cities – large and spaced out, together with unusually high population growth, means that well-located land is even scarcer here than elsewhere. That’s what makes Australia a high capital growth market. Because Australia is a high capital growth market, it is also by definition a low yield market” (Figure 3)11.

Strong capital growth propositions in affordable housing attract capital

Given the minimal impact yields have on overall returns in Australian residential property investments, it follows that local investment opportunities that can optimise for enhanced exposure to capital growth and solve for housing affordability should more readily attract return-seeking private capital with an ESG focus.

Balancing ESG outcomes with financial objectives in affordable housing

While some investors with higher liquidity and income preferences will continue to be attracted to yield based residential property investment opportunities in the affordable housing sector, it is important for investors to consider how rent rises over time, especially where rents are indexed to inflation, could be counter to the overall ‘affordability’ intent of an underlying investment objective. There is also the question of how capital growth in affordable rental investments is realised, without displacing tenants through sales that result in evictions. Future operators have no obligation to maintain assets as ‘affordable’, and as market dynamics change and pressure to realise returns mounts, ESG objectives will be challenged. Given tenants in affordable housing rental schemes tend to be low-income earners, the implications of capital growth realisation events on their ongoing housing needs remains a significant ‘unknown’ for many institutional investors and may pose future reputation risk.

ESG credentials of home ownership can de risk affordable housing objectives

What is clear is that the risk/return trade off in housing is not as straight forward as many other traditional investments. We are seeing this play out through an emerging bifurcation in the affordable housing segment of the residential market. That is, between investment products that primarily derive their return to investors from subsidised rental-income streams and investment products that seek to bolster long-term home ownership, delivering returns linked to superior capital growth returns. It is our view that stronger capital growth returns are accessible through well located, quality controlled owner-occupied assets, with home ownership, as an overall impact objective, core to the ESG thesis.

Against the current backdrop of the Australian housing crisis, our view is that enabling more middle-income Australians to own residential housing assets – rather than rent lower quality, less well-located assets – solves a critical social issue and delivers a more attractive return. Investment models that pursue home ownership as an outcome should be of great interest to those property investors applying a rigorous ESG filter to their portfolio.

Shared equity investment solutions are just one example of new investment models seeking to address this home ownership challenge. They provide private markets with access to the owner-occupied segment of the residential property asset class, as opposed to a tenant/landlord segment. This distinction is important, as data from CoreLogic suggests that capital growth in owner-occupied properties outperforms tenanted investment properties13.

Institutional Investors: The approach to date

Following the lead of similar advanced economies, like the UK and the US, several institutional capital solutions for affordable housing have started in Australia. Locally, these solutions have predominantly focused on affordable rental, namely through Build-to-Rent (BTR) developments.

BTR is purpose built and designed long-term residential rental accommodation which is predominantly owned, managed, and operated by an institutional investor for a long-term investment period. Revenue is generated through the rental of the dwellings as the primary source of income, with additional income generated from opt-in and ancillary services.

BTR is not designed to address attainable home ownership. Like the multi-family sector (US market) and private rental sector (UK market), they are designed for long term, even intergenerational renting, not home ownership.

Offshore, institutional capital has also been active in the Equity Release (ER) market, which provides a cashflow solution for those who already own their home.

ER enables those who own their own home, to unlock equity. The structure can take a number of forms including reverse mortgage, home sale proceeds sharing, and equity release agreement. Revenue is generated via interest payments (typically above standard mortgage rates) and on capital appreciation of the property, when sold.

Locally, Australian superannuation funds are early in their investment journey with attainable housing models, however it is expected that this will occur in the not-too-distant future, mirroring the pathway of M&G14 and Legal & General15 in the UK, who offer similar shared ownership solutions.

Attainable home ownership models

From an investment perspective, exposure to residential property can be obtained from either the supply

side or the demand side. Supply side, development-based models include:

- Build-to-Sell,

- Build-to-Own (Property / Unit Ownership), and

- Build-to-Rent.

Demand side financial structuring models include:

- Equity to Debt,

- Equity Release,

- Second Mortgage Loans,

- Equity Financed Loans, and

- Shared Equity Products.

Turning our attention to those models on the demand side that are intended to address attainable home ownership, they broadly fall into one of the following categories:

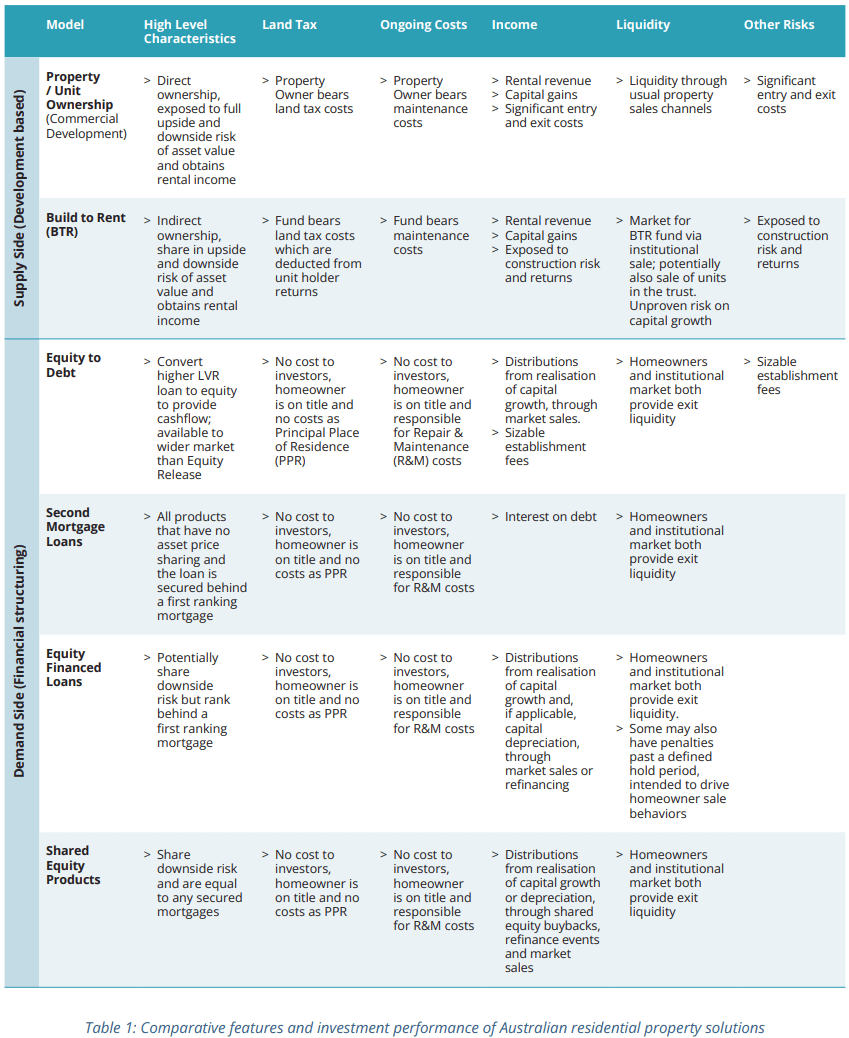

Second Mortgage Loans

Often described as low deposit, no deposit, piggyback, or deposit gap loans, market providers will lend up to 20% of the home purchase price, with the remaining 80% provided as a traditional mortgage. The rates and fees on these deposit gap loans are higher than the 1st mortgage and typically have a shorter life than a 30-year mortgage. It is important to note that this instrument is more about access to the interest rate return, not the underlying return on the property asset.

Equity Financed Loans

These are products where instead of an interest rate, the return on the finance provided is calculated based on the change in value of the property. All products share in the capital appreciation of the property, some at a multiple of the appreciation. A few, typically government run programs, may also share in the downside (at sale or refinance), if the property depreciates in value. These products are a form of debt and if the proceeds from the sale of the property are insufficient to repay the first mortgage and equity financed loan, the borrower may still be liable for the shortfall. These products are subordinate to the 1st mortgage.

Shared Equity Products

These are not debt products. The shared equity provider is pari passu with the homeowner and any first mortgage. The shared equity provider is entitled to a share of the proceeds from the sale of the property (or equivalent, if the product is refinanced at any time) whether the property has increased or decreased in value. Typically, the shared equity provider is entitled to the same share of the property’s sale price as they financed when the property was purchased

Key features of Australian residential housing models

We have compiled a summary view of the demand and supply side models for investors seeking access to the Australian residential property market. Each option presents different characteristics, land tax implications, ongoing costs (including repairs and maintenance), income streams, liquidity profiles and risks. The table below provides a high-level overview across each of these dimensions.

Footnotes

2 https://www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/grants-schemes/first-home-buyer

3 https://www.nsw.gov.au/housing-and-construction/home-buying-assistance/shared-equity

4 https://www.housingaustralia.gov.au/support-buy-home/first-home-guarantee

5 https://treasury.gov.au/publication/p2020-100554

6 https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2023-intergenerational-report

7 Based on KPMG research of Family Office assets (https://www.afr.com/rich-list/you-re-rich-but-are-you-family-office-rich-20231013-p5ec2s) and ATO statistics of the SMSF market (https://www.ato.gov.au/individuals-and-families/super-for-individuals-and-families/selfmanaged-super-funds-smsf/in-detail/statistics/annual-reports/self-managed-super-funds-a-statistical-overview-2020-21/smsf-profile)

8 https://www.superannuation.asn.au/resources/superannuation-statistics

9 https://sqmresearch.com.au/property-rental-yield.php?t=1&avg=1

10 https://blog.stockspot.com.au/rent-or-buy-we-do-the-sums/

11 https://www.pexa.com.au/staticly-media/2023/05/LongView-PEXA-Whitepaper-3-Mobilising-Private-Capital-for-New-Housing-Solutions-sm-1684212151.pdf

12 (ABS, 2021b), (CoreLogic, 2022), (FRED, 2022b), (Zillow, 2022), (BIS, 2022), (RealAdvisor, 2022)

13 CoreLogic – Pain and Gain Report, September 2023

14 https://www.mandg.com/investments/institutional/en-gb/capabilities/real-estate/shared-ownership

15 https://landgah.com/

Disclaimer

The information in this article was finalised in February 2024. This article has been prepared by HOPE Housing Fund Management Limited (HOPE) ACN 629 589 939 (Investment Manager/Manager/Company/HOPE/HOPE Housing) for general information purposes only, without taking into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on this general information, you must consider its appropriateness having regard to your own objectives, financial situation and needs. The information provided is not intended to replace or serve as a substitute for any accounting, tax or other professional advice, consultation or service and nothing in this article shall be construed as a solicitation to buy or sell any financial product, or to engage in or refrain from engaging in any transaction.The Investment Manager is a corporate authorised representative (number 001289514) of SILC Fiduciary Solutions Pty Ltd ACN 638 984 602 (AFS licence number 522145). The authority of the Investment Manager is limited to general advice and deal by arranging services to wholesale clients relating to the Fund in Australia only.

Past performance should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of future performance and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made regarding future performance. Economic conditions may change.

The analysis provided in this article is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable but HOPE does not make any representation or warranty that it is accurate, complete or up to date. HOPE accepts no obligation to correct or update the information or opinions in it. Any opinions expressed in this article are subject to change without notice. No member of HOPE accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct, indirect, consequential, or other loss arising from any use of such information.